The Empire State Building

“Mom, I have a question to ask you.”

“Sure, Joey. What’s up?

“Was John Crivelli really my father?”

Silence. Then a big sigh – the sigh someone would make when they had been running their whole lives, and the truth came out, and they knew the charade was up. The sigh of someone who couldn’t run anymore and was now resigned to the telling the truth.

“I have always wondered when you would ask me that.”

It was a question that had been on my mind my whole life. John Crivelli was short. Fat. Big round face. Wiry black hair. Deep set, dark, beady eyes. A swarthy, paunchy, dark‐complected Italian just one generation removed from the old country.

Me? Tall. Fair. Hazel eyed. Narrow faced. Lean and lanky. Athletic. I would look at pictures of my father and wonder, “did I inherit any genes at all from this man? Anything?”

So this was a question that had been percolating for some time. Plus my mom had dropped some not‐ so‐subtle hints. There was the story she told about the day she found out she was pregnant – how she took my sister to see the movie “Dumbo” and cried the whole time. My sister would chime in, “I didn’t know why Mommy was crying so much; the movie was not that sad.” I would ask why she cried and she would say, “I was done with bottles, diapers, your sister Fran was in school and I just didn’t want to go back to all that.” And then always the caveat, “But I love you and wouldn’t change a thing.”

As if that statement would make right the fact that I was unwanted from the start.

Then there was the time – and I don’t remember how this came up in conversation – that she told me that she tried to have a miscarriage. “I just didn’t want another baby. I would go downstairs and jump up and down and try to lose the baby. I would eat chalk – an old wives tale that this would cause a miscarriage – and I would gag and gag on the chalk but eat it anyway.” And then, “But I love you and wouldn’t change a thing.”

I don’t know what gave me the courage to ask it in that particular phone call, on that particular afternoon. But it bubbled up and out and now was hanging out there like a big hair ball.

Another sigh. I already had my answer.

“So?”

“First I want you to know that I love you dearly and wouldn’t change a thing. Not one thing…

But I always wondered when you would ask this question.”

More silence.

“No, John was not your father.”

“Who was my father?”

“Martin. His name was Martin Weiner.”

I waited. Something instinctively told me to just wait for her to open up.

“Joey, please promise me you won’t hold it against me.”

That was another of her throwaway statements: Promise you won’t hold it against me. Any time she messed up, any time she knew that she had caused irreparable damage to me, she made me make this promise. The most noteworthy was the time John Crivelli died.

Mom and John had split up 10 years earlier, and I hadn’t seen or heard much from him since then. And I know I should have taken responsibility for finding out when the wake and funeral were, but I didn’t. I was 19. I was a clueless teenager. And I just assumed that my mother would let me know where I had to be, when I had to be there.

So, she told me that the wake was Thursday night at 6:00 and the funeral was Friday morning at 10:00. I showed up at the 6:00 wake on Thursday night only to find out there was a second, earlier wake and a bunch of my friends had shown up to pay their respects to my father…and I wasn’t even there. I went to sign into the guest book – just like any of the other visitors – and noticed all these signatures from earlier in the day. I turned to my mom and said incredulously, “There was an earlier wake???”

She withered and then, “PLEASE DON’T HOLD IT AGAINST ME!!!”

My mom and I had an up‐and‐down relationship, sometimes good, sometimes bad. By the end we made our peace. But this was one of the tougher moments.

So here we were again, with my mom telling me that she had done her best all my life to keep the truth about my paternity from me, and that she had hoped against hope that she could take this secret to the grave. And once again asking me for pardon and forgiveness. For a promise of everlasting filial love despite her failings. I did the merciful thing.

“I promise.”

“Martin Weiner was a beautiful, beautiful man. I worked for him when I was in my 20s and we saw each other off and on for years. He was a beautiful man. I loved him.”

“I met him when I was working as a telephone operator at one of his companies. Mar‐Tex. It was my first day, and he walked in and said, ‘Aren’t you a beautiful ray of sunshine!’ and I just melted. We started seeing each other almost right away. Martin was your father. And you look just like him. He was so handsome too.”

“Is he still alive?”

“Nooooo, he’s long gone,” she said in her whiskey drawl. “He died when you were 4 years old.”

“Did he know about me?”

“Yes, he knew about you. I used to take you to see him, and he would hold you on his lap.”

“Did John know that I wasn’t his kid?”

“No, John didn’t know. He always suspected something between me and Martin, but he did not know that you weren’t his son.”

Mom went on to tell me what she could remember about Martin, which wasn’t a whole lot considering they had a decades‐long affair. He owned a textile mill in Paterson, NJ. He lived in Clifton, NJ. He had a brother, Jess. A wife, Tilly. And two daughters, Joan and Iris. He invested in real estate and owned the Empire State Building.

The Empire State Building!! I loved The Empire State Building. Living in Clifton, that building was omnipresent, because you could see the New York Skyline from just about everywhere in the town. It was called “Clifton” because it was literally built on a cliff that overlooked the New York skyline. Clifton was a hardscrabble town, with nice neighborhoods (where we lived when I was a little kid) and not‐so‐nice neighborhoods (where we lived after mom and dad split up and sold the house.) About once a year, mom and dad would pack us up in the station wagon and take us to New York City for a show, or the circus, or ice skating at Rockefeller, and invariably we would also visit the Empire State Building. The view from the top was amazing, and the wind always howled, and the sharp points on the wrought iron grates that prevented would‐be jumpers from climbing over the top always scared me.

To learn my biological father was an owner of the Empire State Building was on one hand quite a shock. On the other hand, it was pretty typical of my mom to exaggerate. I had my doubts about the Empire State Building part of the story.

‐‐‐‐‐‐‐

I walked downstairs. My wife Deanna could sense the heaviness. She could see it in my eyes.

“What’s wrong Joe?”

Silence.

“Joe, what’s wrong?

“I….I….just talked to my mom.”

“What, Joe? What’s wrong?”

“You know how you always said I had a Roman nose?”

I have an Italian last name, and Deanna was from an Italian family, and she liked my Italian‐ness. But other than my last name, there was nothing Italian about me. She and her mom latched onto my nose. I have a prominent nose, which they convinced themselves was a Roman trait. Nevermind that my family supposedly came from Calabria, it made sense to them.

“Yeee..eees?”

“It’s not a Roman nose.”

“What?”

“It’s a Jewish nose.”

“I don’t follow.”

“I finally got the courage to ask mom if John Crivelli was really my father. She told me the truth. She had an affair with this guy, and he’s my father. His name was Martin Weiner.”

“Wow. WOW.”

“He was a Jewish businessman from New Jersey.”

“Wow.”

Silence.

“How do you feel about that?” She came over and sat down next to me and touched my hand.

“I don’t know.”

“That’s big.”

“Yeah. Too big for me to grasp right now.”

“It he alive?”

“No. He died when I was 4.”

“Did he know about you?”

“Apparently. Yes. She said she used to bring me over to see him.”

“Did your father…I mean, did John…know?”

“Apparently not. She says he didn’t, anyway. But that could explain a lot of things.”

“Wow. Joe. I’m so sorry.”

“It’s not your fault.”

“No, I mean I’m sorry you have to find this out. Now. This late in life.”

“It sucks.”

‐‐‐‐‐‐‐

Several years went by. I would from time to time try to find some additional information about Martin, some talisman or touchstone to connect me with him and help me, in some small way, to know my father. All my searching was a dead end. On Google, I found a legal review article about an intellectual property lawsuit against his company. The case, Peter Pan Fabrics v. Martin Weiner was a landmark case in trademark infringement.

Other than that, I could find nothing. No evidence that he existed, no articles about him or his business, nothing validating my mom’s unbelievable claim that he owned the Empire State Building. Nothing on his daughters Joan Weiner or Iris Weiner. Nothing on his brother Jess Weiner.

Until December 2006.

It was the Christmas season, and I was at work but nothing much was happening. I was goofing off, and all of a sudden I got the idea, “Hey. I haven’t tried to find any information about Martin Weiner in a while. Let me see if I can find anything today.”

And with that, the floodgates opened. The first Google search delivered an obituary from the New York Times’ website.

I blinked as I looked at the headline. “MARTIN WEINER, 65, MAKER OF TEXTILES”

That’s him. That’s his obituary. My heart started racing.

I clicked on it, but it was a paid article from the Times’ archives. Shaking, I took out my wallet.

I found him. I may finally see my father’s face.

I paid for the article. When it downloaded, it seemed to take an eternity.

MARTIN WEINER, 65,

MAKER OF TEXTILES

Martin Weiner, a textile manufacturer, real‐estate man and philanthropist, died last night in Methodist Hospital in Houston after an unsuccessful aorta transplant operation.

Mr. Weiner, who was 65 years old and lived at 140 Hepburn Road in Clifton, N.J., was stricken with a ruptured aorta last week after his wife, the former Tillie Frankel, died.

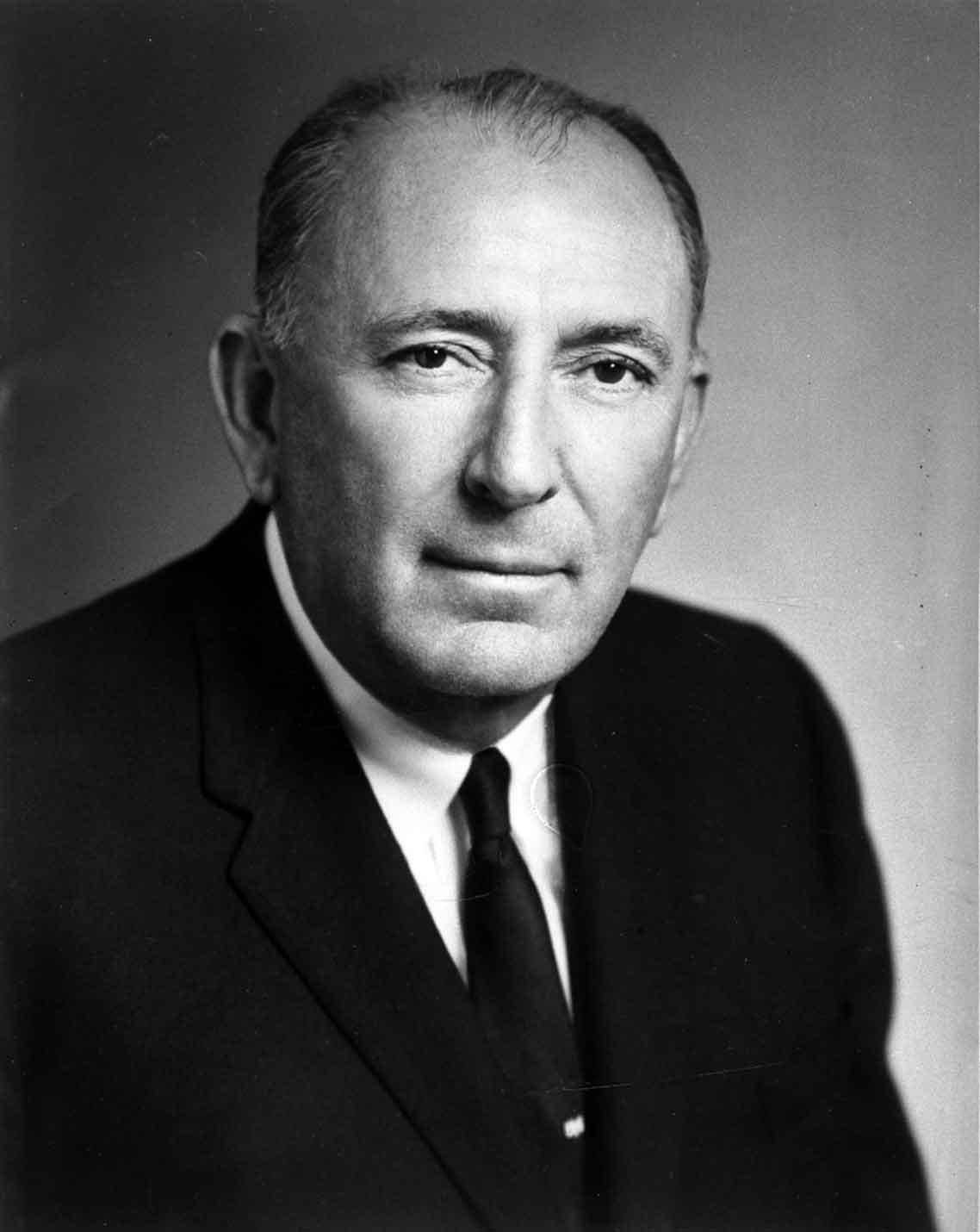

Mr. Weiner bought a small textile mill at the age of 26 and converted it to rayon in 1929 because of the fluctuations in Japanese silk prices. He was head of the Martin Weiner Realty Co., with interests in major properties across the country, including the Empire State Building.

He was a member of the board of trustees of Fairleigh Dickinson University and of Brandeis University and was president of the American Friends of Kyung Hee University in South Korea. He also served as an industrial consultant to the Department of Commerce and as an evaluator for the United States Information Agency.

He is survived by two daughters, Mrs. Sanfurd Bluestein and Mrs. Jack Konner, two sisters, Mrs. Florence Housman and Mrs. Sadie Wohlman, and four grandchildren.

No picture, but there it was. The guy was a real player. And he did own part of the Empire State Building.

I spent the rest of the day chasing down leads in the obit. There were many. I searched the Fairleigh Dickinson website, the Brandeis website, I learned about my half sisters.

And within hours, I had a picture of my father in my email inbox and on my fax machine.

A search on the Fairleigh Dickinson website indicated that the library at the Teaneck campus was named after Martin (“The Weiner Library”.) I called the library to see if there were any pictures of Martin hanging around. The librarian indicated that she had a newspaper article commemorating the library’s dedication, and she faxed it to me within minutes.

A search on the Brandeis website indicated that the archives had a picture of Martin. A phone call to the university archivist led to a high‐resolution scan of the photo being emailed to me.

It’s hard to explain the feeling that a man in his 40s gets when he sees his father’s face for the first time. Partly, there was relief. After a lifetime of looking at images of my ‘father’ John Crivelli and wondering what – if any – of his DNA I had in me, seeing the picture of Martin Weiner told me that I really did have another half to me. I could see where I fit, I could see the double helixes forming in me as Martin’s seed met Arlene’s egg and a new human being – me – came to be. I could see how I came together in this universe

.And at the same time, I was pissed. PISSED. This guy was a multi‐multi‐millionaire. He was a player in the New York business community. He knew about me, he knew he had a son, and he left me nothing. NOTHING. Not even a note, a letter, a picture, a memento that someday would enable me to connect with him. He never faced any consequences for his actions. He swept me under the rug. He never did the right thing and acknowledged to the world, “I screwed up. But I’m going to do the right thing by this boy. He is my flesh and blood.”

My mother - same deal. She was so ashamed of herself that she couldn’t come forward, tell the world that her son was Martin’s boy, and follow whatever the legal process in those days was for establishing paternity – which would have enabled her to become a wealthy woman in the process. But no. She was too ashamed of the truth.

With the leads from the obit, I learned that of Martin’s immediate family, only one person was still alive – my half‐sister Joan, a successful person in her own right. She had become a famous journalist, a commentator and pundit on political issues, and dean of a famous journalism school. She still owned the Weiner share of the Empire State Building, and she was a published author of two arguably spiritual books. She was the only person in the world who held the key. The only person who could tell me: “What was my father like?”

At the same time, there was an urge to be a part of a family. I had fantasies in my mind of meeting Joan and being welcomed into a family where by flesh and blood I belonged, but where by moral standards I was an embarrassment, a black stain on the family tree…the bastard child.

But times had changed, hadn’t they? I had even read an article about John Major, the former prime minister of Great Britain, discovering a half‐brother late in life and being overjoyed. Would Joan be overjoyed to know that she had a brother, that there was someone in the world who was connected to her and who shared her flesh and blood? Or would she be brokenhearted on learning that Martin had cheated on Tillie? Or would she be fearful that I was just some money‐seeking scammer looking to profit? Should I let sleeping dogs lie? Or should I demand my rightful place in the world and demand that those in the world who could do so acknowledge it?

At the root of it, I really just wanted to know my father. But I will be honest that having grown up poor, having had to earn every dollar I ever spent from the time I was 14 years old, having had nothing at all given to me and having had to find my own way in the world – chose my own college, choose my own major, choose my own career with no helpful input whatsoever from a parent – there was something intriguing about finding I was the son of a millionaire. By rights, I should have a piece of the building. By rights, when Martin’s assets were divvied and sold, I should have had a seat at the table and a share of his life’s work. My children should be provided for, and their children. I should be rich, not poor. It was tantalizing.

Finding Joan online was not hard. Once I knew to search for Joan Konner instead of Joan Weiner, I found her email address, various and sundry articles about her successes in life, her marriages, her children, her books.

Rightly or wrongly, I sent her an email and a letter asking if she would be willing to meet. She politely declined through a lawyer who sent me a tersely‐worded letter back:

Dear Mr. Crivelli:

I represent Joan Konner and write in connection with your recent communications with her.

Please be advised that Ms. Konner does not wish to receive any further communications from

you.

Etc.

Ms. Konner does not wish to receive any future communications from you. That stung. That really stung. The only living tie to my biological father, the only person who could help me learn about him, the only person who held the keys, my flesh and blood. My sister. My kin. Not only unwilling to meet but clearly didn’t want any parts of me.

Rejection.

I was devastated. I know that it was probably scary for her to hear from someone claiming to be a blood relative, especially considering she is elderly and wealthy. I understand that. But years later, the pain of her rejection is fresh.

Still today I can feel the pain of opening that envelope in my driveway on that midwinter day and reading those cold, cold words. Hearing that steel door slam shut on any hopes of discovering my father.

Ironically, Joan had written books and edited television documentaries about love, about family, about life and faith and connectedness. She worked on a documentary about Joseph Campbell, in which the famous author, educator, and philosopher talked about the importance of the quest for father, the quest that every man goes on to find the true nature of his paternity. I watched it in wonderment. In it, a wide‐eyed Bill Moyers interviews a thoughtful Joseph Campbell, and they talk about the father quest:

MOYERS: What impact has this father quest had on us down through the centuries?

CAMPBELL: It’s a major theme in myth. There’s a little motif that occurs in many narratives related to a hero’s life, where the boy says, “Mother, who is my father?” She will say, “Well, your father is in such and such a place,” and then he goes on the father quest…the mother’s right there. You’re born from your mother, and she’s the one who nurses you and instructs you and brings you up to the age when you must find your father.

Now, the finding of the father has to do with finding your own character and destiny. There’s a notion that the character is inherited from the father, and the body and very often the mind from the mother. But it’s your character that is the mystery, and your character is your destiny. So it is the discovery of your destiny that is symbolized by the father quest.

MOYERS: So when you find your father, you find yourself?

CAMPBELL: We have the word in English, “at‐one‐ment” with the father. You remember the story of Jesus lost in Jerusalem when he’s a little boy about twelve years old. His parents hunt for him and when they find him in the temple, in conversation with the doctors of the law, they ask, “Why did you abandon us this way? Why did you give us this fear and anxiety?” And he says, “Didn’t you know I had to be about my father’s business?” He’s twelve years old‐ that’s the age of adolescent initiation, finding who you are.

Excerpted from The Power of Myth; Joseph Campbell with Bill Moyers; Anchor Books, 1991.

My half‐sister stood behind the camera, worked in the film room putting these interviews together, and was apparently unmoved. Because when her own kin, her own flesh and blood called to ask for her assistance on his own father‐quest, she had a lawyer send him a letter saying, essentially, “Get lost.”

I remember receiving that letter in the mailbox and knowing who it was from. I tore the letter open right at the mailbox, in the dark, in the cold, in the middle of the street. And I remember reading that one‐paragraph letter and knowing that the door had clanged shut permanently and that it was over, that my father‐quest had hit a dead end and that there were no other paths to go down.

Other boys could have relationships with their fathers. Other boys could have fond memories of catches with dad or fishing trips or ball games, or vacations with dad or going to the bar with dad for a beer or hikes or swims or canoe trips. Of words of wisdom passed down innocuously over the dinner table while dad tucked into his spaghetti or borscht or bangers and mash. Other boys could remember what their dad smelled like – his cologne or the booze on his breath or stogies or sweat.

Other boys could remember dad helping them pick a college or teaching them the birds and the bees or teaching them how to draw a golf ball around the dogleg. Other boys could remember hunting trips with dad and the frustration that they didn’t even see a buck, let alone get a shot at one. Other boys could remember the look of pride on dad’s face when they made their confirmation or bar mitzvah or got drunk for the first time or got laid for the first time.

For that matter, other boys could remember getting their asses kicked by dad or dad being emotionless and unavailable and drunk in the armchair or dad talking in hushed tones on the telephone to his mistress or dad coming home from work late and going to bed early or dad telling them how much they had failed, how they could never measure up; how them they should have caught that fly ball to end the game instead of dropping it and allowing the other team to score the winning run. And those boys would remember how hard it was to make their peace with dad, to forgive the old bastard for his failings and love him anyway and know that after all, he was dad. Flesh and blood. Kin.

Other boys had a dad. Not me. This haunted me even when I thought I had a dad. It’s hard enough to grow up male, to learn how the game is played, to develop strategies for living in mine‐is‐bigger‐than‐yours world. I could have used Martin’s help. He was a player. He was a successful businessman who started a new business. I could have used his counsel on what college to attend, what major to select, how to deal with the bullies on the playground and outmaneuver them with wit and intellect, how to defend myself, how to gain the upper hand in an argument or debate, how to sense when someone has your back and when they are about to stab you in it. For Martin to have achieved what he achieved, even if he did have a head start, he had the arcane knowledge to navigate the landmines of human relationships and win more often than lose. And he left me, his only son, to fend for myself.

‐‐‐‐‐‐‐

I couldn’t let it go.

A few years later, I found out that Joan was speaking at an author’s convention in Albany, NY. The event was open to the public and she was on a panel. So, I went.

After her talk, I approached her tentatively.

“Joan. Hi. I’m Joe Crivelli.”

“Oh. What are you doing here?”

“Well, I wanted to meet you. And I’m a writer too, so I thought I’d check out the conference.”

“Oh.”

“Joan, you remember that documentary you did about Joseph Campbell? How he talks about the importance of the father‐quest in the life of a man? That’s all this is about. That’s the only reason I reached out to you. I just want to know about my father – what kind of man he was.”

With that she opened up a little.

“My father was a wonderful husband and father. That’s why it was such a shock to get your message. I could not imagine my father doing something like this.”

“Everybody makes mistakes.”

“He was a wonderful father. I loved him very much. My mother was sick for nine months before she died. He was at her bedside taking care of her the whole time. If you could have seen it you’d never believe he would have had an affair. So I can’t believe it. I won’t. That’s not the man I knew.”

We talked a little more, but that was all I needed. To hear that Martin was a good man, that he loved his family, and his family loved him, gave me a lot of peace. Even if he didn’t do right by me, there was goodness in him and so there was goodness in me. I left the convention feeling uplifted and happy. I was glad I went. I was glad to meet my sister – she seemed like a nice person too, and I understood why she reacted the way she did. I was happy to let things be from that point forward. I sent Joan a nice ‘thank you’ note, and left things alone after that.

‐‐‐‐‐‐‐

Almost a year later, the receptionist at the company I worked for buzzed me in the middle of the afternoon.

“Joe, there are some men here to see you.”

“I don’t have any appointments. Did they say what for?”

“No.”

I went downstairs to the reception area, and two scary‐looking Special Forces‐type alpha men in business suits were standing there, looking sinister.

“Can I help you?”

“Are you Mr. Crivelli?”

“Yes.”

Can we talk confidentially for a moment?”

I took them into a conference room off the reception area, and they sat down and placed a rather large file folder on the table.

“We are here representing Ms. Joan Konner. You have been harassing Ms. Konner, and it needs to stop now.”

“I haven’t been harassing her. She’s my sister.”

“She denies that she is your sister. Last year, you accosted her at a speaking appearance.”

“I didn’t accost her. It was a public event. I listened to her talk and said hello afterwards. We had a nice conversation.”

“She claims she was very scared of you, that you did some things that led her to be afraid. If you ever make contact with her again, you will regret it for the rest of your life.”

With that, he gestured to the large file folder. The implication was clear. In that folder was all the dirt they had been able to dig up on me. I’m sure there was plenty.

I don’t remember much of the conversation after that. I went back to my office, closed the door, and broke down and cried. Any good feelings I had from my brief conversation with Joan dissipated, and all I could feel was injustice. Even today, as I write this many years later, the pain is still fresh and raw.

‐‐‐‐‐‐‐

With all the paths to Martin closed, over time, I got closure. It took time, and hard work, but I eventually got peace around the whole issue.

I did the work I needed to do to process these emotions; to clean my side of the street and make amends for any harms done to the family members that are in my life; and to put pain in the rear-view mirror. I deployed every tool I could find to make this happen. I sought therapy and counseling; I talked to friends; I’ve been in the recovery community since 2001, and I worked the 12 steps specifically on these issues. I wrote about it – which became this article. And at one point I did stand‐up comedy as a hobby, and even used this story as the opener for my routine; as they say, laughter is the best medicine:

“Hi I’m Joe Crivelli, and I know what you’re thinking. ‘Joey Crivelli from Philly, he’s probably a made guy, a goodfella, a Mafiosi.’ But the reality is I have no Italian blood in me, my father was a Russian Jew. So now you’re thinking, ‘Then how did he get an Italian last name?’ And THAT, my friends, is a sordid story and a bit of family history that my mother would NOT appreciate me sharing in public!”

‐‐‐‐‐‐‐

In February 2018, I got a message on 23andme.

“Hi, I was wondering how we are related…my grandmother was a Weiner…this says we are first cousins….I am in New York, how about you? I am 61 years old…Would love to hear about you... Blythe

I stared at the message, pondering how to reply. A genetic test on 23andMe had indeed confirmed that I was not Italian, but rather 48.6% Ashkenazi Jewish on my father’s side. But this was the first direct contact I’d gotten from someone on the Weiner side of the family. And the first hard proof that I was truly connected through DNA to the Weiner family.

23andMe showed that Blythe and I were first cousins, one removed, sharing 7% of our DNA. In fact, after my mother, daughter, and sister, she is the person I share the most DNA in common with.

I wrote back:

Hi Blythe, Thank you for your message. The first thing you should know is that I’m not a “welcomed” member of the Weiner family. According to my mother, Martin Weiner was my father. I found this out about 12 years ago, so very late in life (I’m 52 now). I’m inclined to believe my mother because I look a lot like Martin (I’ve seen a handful of pictures) and nothing like the man I thought was my father (John Crivelli.)

I did try to connect with my half sister, Joan Konner, years ago but was told in no uncertain terms to get lost - one of the most painful chapters of my life.

If you’re still interested I’d love to learn more about that side of my family.

Joe

To my surprise and joy, Blythe was more than happy to talk and build a relationship, and share with me what she knew about the Weiner family, which wasn’t much. After Martin’s death, the family scattered to the winds, and very few kept in touch. She and her mother (who was Martin’s niece) lost touch with Joan and the other surviving members of the family.

Nevertheless, Blythe became a good friend. She and I and her husband Paul met for dinner when I was on a business trip to New York City and connected on Facebook and such. She is a warm, loving, caring person. She helped me to heal from the cold shoulder I had received from Joan.

---

Every movie or TV show set in New York City shows the Empire State Building. It is symbolic of New York City and establishes place the way the Eiffel Tower, or Big Ben, or the Taj Mahal do. And so I can watch TV at the end of a busy day, and if the show is set in New York, I’ll see that damned building. It used to make me sad.

Today, the Empire State Building symbolizes something else entirely. It reminds me that I was created for a reason. God went to great lengths to bring me into this world. He kept me safe in the womb of a woman who didn’t want to be pregnant. He has protected and guided me every step of the way. He revealed the truth to me slowly, as I was ready, and gave me time to process my feelings and grow. And He has blessed me far beyond what I deserve. Whatever mom and John and Martin wanted, I’m here. I belong. I’m happy. I’m strong. I’ve gotten to a place where I no longer have any anger about the situation. I love and respect the man I see looking back in the mirror – he’s a brave, strong man who’s overcome much to get to where he is and who hasn’t been afraid to make radical life changes when those changes are called for.

I think, ultimately, that God protected me from two men who were not suited to be fathers – one, a sullen, emotionless, and unhappy alcoholic; the other an irresponsible philanderer who took his double life to the grave.

So, I did have to find my own way and navigate my way through life without the help of responsible adults. And you know what? I did just fine.

So those times when the Empire State Building flashes across the screen and reminds us that the movie or show is set in New York, I’m reminded that today, I live, and I live for a higher purpose.

Epilogue

My half-sister Joan Konner died on April 18, 2018, at age 87. Like her father before her, Joan was a player. Her passing was noted by extensive obituaries in the New York Times and on the website of the Columbia Journalism School, where she served as Dean for nine years.

My mother Arlene Rodney died of lung cancer on February 16, 2019 at age 93. Mom was a rebel until the very end, even sneaking a pack of Marlboro Lights into the hospital in her bathrobe. She died peacefully, surrounded by family members who loved her. I consider it one of the great accomplishments of my life that when she passed, I had nothing but love and admiration for her in my heart.